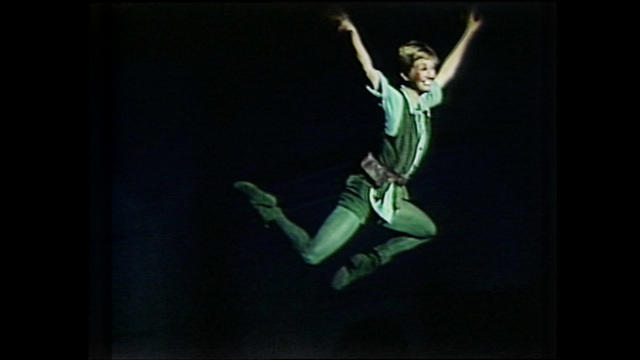

▶ Watch Video: Sandy Duncan on life before and after “Peter Pan”

In the 1970s Sandy Duncan was everywhere, a capital “E” entertainer starring in family comedies like “$1,000,000 Duck,” earning an Emmy nomination for her performance in “Roots,” teaming up with those meddling kids of “Scooby-Doo,” and high-kicking with a gaggle of Muppets.

“I mean this as high praise: you were kind of made for The Muppets,” said correspondent Mo Rocca.

“I was!” Duncan replied. “I related more to them than a lot of actors I’ve ever worked with.”

And during commercial breaks, she hawked Wheat Thins crackers, though it turns out it’s a rival snack food she now prefers: “I love Triscuits,” she said.

“Is this an exclusive?” Rocca asked.

“Yes! This is an exclusive!”

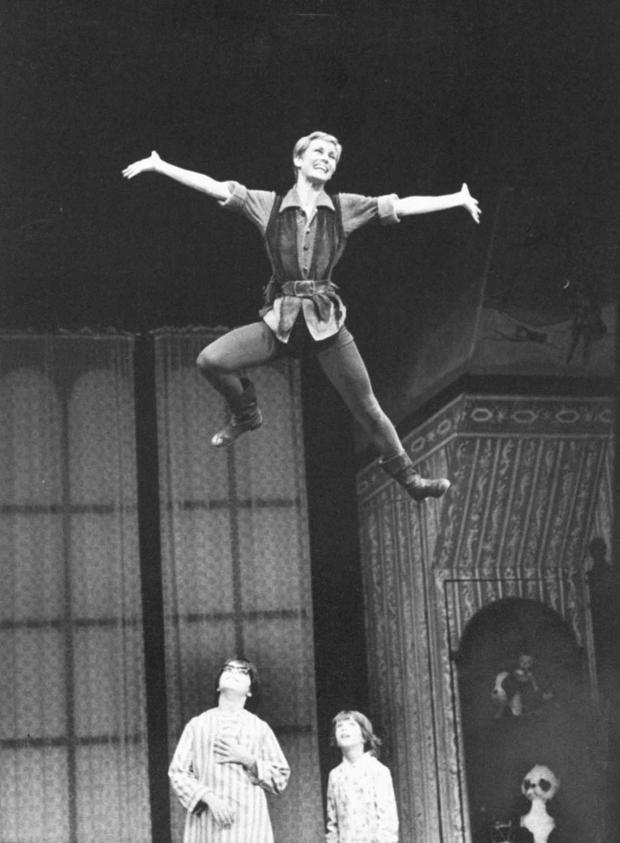

But for many, Sandy Duncan is suspended in time as the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up, dazzling audiences in the 1979 revival of “Peter Pan,” in 554 performances. “I felt joy every time I did this,” she said. “I don’t think I had a bad show.”

She’s not the bragging type, but “You can still crow?” asked Rocca.

“I can still crow! Dance, not so much.”

In fact, she’s still kicking: “Pretty close! You’re taller. Your legs are longer! Now I’m aggravated. OK. Cut!”

The dancing began when Duncan was a kid in New London, Texas. “It’s a teensy oil town. And that’s where I was born, and went ’til first grade. It literally is the VFW hall, a grocery store, a drug store, the bank, and then a church, and a church, and a church, and a church, and a church. Then, you’re outta town.”

That’s where Duncan danced in her first recital, when she was just five years old. “I didn’t have the lead part; Nona Kay did. We were sorta that back-up girls that would go, ‘That’s right, Nona Kay, that’s right!'”

In third grade, she moved to the “big city” of Tyler, Texas, the Rose Capital of America, and naturally a place with lots of parades. “We had some ugly queens, I’ll tell you. ‘Cause it’s whose daddy had the most money.”

Duncan, however, had the most talent, and when she was 19 she headed to New York. “I moved into this place called the Rehearsal Club, which was just for young women. It was $32 a week. I started getting work right away, which is lucky, because it’s not always the case. And also, I couldn’t audition. Never could, I still can’t. I stink.”

She auditioned well enough, though, to book a series of commercials for United California Bank that got her noticed for her quirky sense of humor.

Rocca asked, “The impression of you as being perpetually cheerful, did that ever irritate you?”

“Yes! of course it did, because it’s far from the truth. Don will tell you that!” she laughed.

Don is dancer and choreographer Don Correia, Duncan’s husband of 42 years. They have two sons and live in Connecticut.

Rocca asked, “Is there singing and dancing that goes on in this house?”

“I grab her occasionally and she goes, ‘Get away from me!'” Correia laughed.

Duncan said, “We tried to do a jump about two or three weeks ago, and I said, ‘Let’s just see if we can jump.’ Well, it wasn’t so easy.”

“It was okay getting up, but then when you land, your whole body just shakes,” he added.

Before they were married, they were dance partners.

What did it feel like to dance with each other? “You just knew you were never going to fall,” Duncan said. “You were never going to be dropped.”

In the 1983 show “Parade of Stars,” in which they performed as Irene and Vernon Castle, Duncan said, “We had to do these really incredibly fast turns. He’s just sure.”

“She’s a very strong woman,” Correia said. “She has been through a lot. It’s made her stronger and stronger. And you know, she keeps saying, ‘Oh, I can’t do this. I can’t do that.’ Well, she can.”

In this web exclusive, Sandy Duncan describes winning a role from Agnes de Mille:

Duncan’s resilience was proven long ago. Back when she was 24, she was cast in her own sitcom on CBS. “Funny Face” was a hit. But three months before wrapping the first season, Duncan just knew something was wrong: “I would get these hideous headaches that I could barely function. And then my eye started getting like I had Vaseline over one of my eyes. And they kept saying it was nerves, because it’s my first series. And I kept going, ‘No, I’m hyper. But I’m not nervous.'”

One doctor recommended sleep: “I thought they were gonna give me a shot, and I’m never gonna wake up.”

And so, she visited more doctors: “And of course, there’s no CAT-scan and no MRI. They didn’t exist. And they found it in the surgery, that there was this big tumor that was attached to the orbit of my eye. They severed the optic nerve. And that’s why I have no vision.”

No vision at all in her left eye.

Rocca asked, “Forgive me if this is too graphic, but how did they even get in there?”

“They sawed the top of my head off,” Duncan said. “I have holes and scars all over the place. And then they stapled it back on. I had to wear a wig for almost a year. And everyone thinks that I lost my eye. And I go: No, I’m sorry, I didn’t. You know, no, it’s not a prosthetic.”

As she made clear in her program bio for a 2008 production of “No, No, Nanette,” Duncan does not have a glass eye. But she did lose her depth perception. “It interferes with a lot of things,” she said. “Just picking up this glass, even yet, and that was what, God knows how many years ago.”

“Fifty years ago.”

“Fifty years ago. Thanks, Mo! And I have to really concentrate to get the glass, or to pour something into something, you know. My biggest problem is my self-consciousness about another person’s comfort.”

It’s easy to forget that Duncan’s greatest triumph happened after her brain tumor. In his review of “Peter Pan,” New York Times theater critic Walter Kerr described how the wires seemed to disappear when Duncan took flight: “She just lets go of gravity, gracefully and gleefully, and lets the mechanical equipment catch up as best it can.”

Rocca said, “That joy and passion it seems like has driven you a lot.”

“I’m not sure what you were meaning about wires,” Duncan said. “What – ?”

“Oh, he said, I was rereading the New York Times review – “

“But I mean, what wires?” she laughed.

Story produced by Jay Kernis. Editor: Steven Tyler.