▶ Watch Video: Robert Moses, the man who rebuilt New York

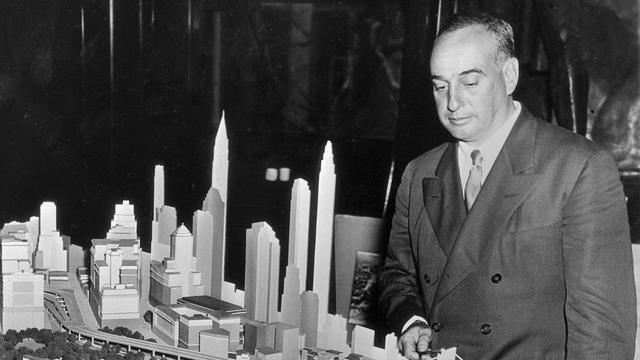

If you don’t know who Robert Moses was, this picture of a scowling giant straddling New York City’s vast sprawl will give you a hint.

Actor Ralph Fiennes stars in a play about Moses opening this week, in the city that is what it is – even today, the good and the bad – because of the nearly unchecked power Moses had for more than 40 years to shape it.

Moses (Ralph Fiennes): “I did what no one else could co, and it stands, providing a frame for the way New Yorkers live, giving them a structure that’s going to last”

The play, “Straight Line Crazy,” by British playwright David Hare, is currently at The Shed theater in New York.

Fiennes told correspondent Martha Teichner, “What I like about the play is the provocation of it, is the provocation of a man who challenges you to like him. He’s done stuff for people; he’s also done terrible stuff to people.”

A partial list of Robert Moses’ public works in New York City and beyond includes more than a dozen great bridges, and 627 miles of roads.

Robert Caro interviewed Moses seven times for “The Power Broker,” his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography. “When you were in his presence, one of the things you saw was genius. The other thing that you saw was, ‘Don’t get in my way.’

“He’s raised to power by the first Irish-Catholic governor, Al Smith. He was the first person who listened to Robert Moses’ ideas.”

In 1924, Smith, the popular, cigar-chomping product of New York City’s immigrant slums, began appointing the Yale- and Oxford-educated Moses to commissions that enabled him to start accumulating the power to build an empire.

Backed by the governor, Moses set his sights first on Long Island. As Fiennes dramatizes in “Straight Line Crazy,” Moses declared, “I’m in a hurry to help, to help the millions out there who have no access to a good life. And if a few fences get kicked over in the process, does it really matter?”

Moses strong-armed his way across the island, seizing land for two scenic parkways. At the end of those parkways, he built his first public works masterpiece: Jones Beach, a multi-million dollar playground of beach with not a roller coaster in sight, and parking for 17,000 cars.

Jones Beach opened in 1929, packed with recreational facilities, along 6.5 miles of white sand, but accessible essentially only to the white, middle-class who could afford cars. Moses made sure there would be no train to Jones Beach, and deliberately built the overpasses on his parkways so low buses had to get there another way.

The first of Moses’ commandments for progress: Thou shalt drive. That meant constructing more and more expressways.

Caro said, “It’s like Picasso in front of a canvas. He sees this whole area with whatever number of people as one picture.”

“But over time, every time he built an expressway, it was overcrowded the minute it opened,” said Teichner. “Did he ever change his vision to reflect the change in the times and the circumstances?”

“The answer is absolutely not,” Caro replied.

Nothing stood in the way.

In “The Power Broker,” Caro documented what happened when Moses slashed through a one-mile stretch of the East Tremont neighborhood to build the Cross-Bronx Expressway, leaving thousands of people nowhere to go, in what looked like a bombed-out war zone.

“The human tragedy caused by that one mile, out of all the miles that he created,” Caro said. “He’s saying he’s relocating the people humanely. In fact, he’s doing nothing to relocate the people. He’s just throwing them out. He did it over and over again – threw out of their homes 500,000 people. Just think what that is.”

How come nobody stopped him? They couldn’t. Moses was appointed, not elected, to positions of enormous power that put him beyond the reach of the eight New York City mayors and six governors he outlasted.

Caro said, “In a democratic society, his power had nothing to do with democracy. With that anti-democratic power, he shaped the greatest metropolis in the western world.”

Moses said in 1964, “We don’t pay too much attention to the critics. They never build anything, no critic ever built anything.”

And that was just it: Robert Moses did build things, and not just roads. Moses-style urban renewal was copied all over the United States. To people whose neighborhoods he didn’t destroy, he was a hero … until he wasn’t.

One obstacle in his path: Manhattan’s historic Washington Square Park. The park would become in effect an on-ramp to his planned expressway across lower Manhattan. Fiennes said, “Traffic would come down Fifth Avenue and then it would continue right through here, right under the arch. He would have completely destroyed [the park].”

But instead of poor people who had no clout, the opposition included Eleanor Roosevelt. Visible and vocal among its leaders was activist Jane Jacobs. In the play Jacobs declares, “We need war, full-out and flat-out, to stop this hideous violation which Moses is planning.” They did stop it.

Robert Moses ran the 1964 New York World’s Fair, but it was a financial failure. By 1968, he had been maneuvered out of power. He died in 1981, at 92, embittered.

In “Straight Line Crazy” Moses states, “And now, of course, it’s suddenly fashionable to dislike me, because I’m the dirty bastard who pushed through the things democracy needed, but which democracy couldn’t deliver. And secretly, people know that. They know I’m necessary.”

But was his creation worth the cost?

Caro said, “The city that we’re living in today is still, for better and for worse, his city.”

For more info:

- “Straight Line Crazy,” at The Shed’s Griffin Theater, New York City (through December 18)

- “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York” by Robert A. Caro (Vintage), in Trade Paperback, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound

Story produced by Reid Orvedahl. Editor: George Pozderec.